Fiction is the real truth

There is a question I’ve always been interested in as a writer, perhaps more so than any other. What is real? To be specific, my interest is in the questions arising from the relationship between fiction and reality.

I explore these questions in my debut novel and it is a common thread in the literature and art that I am drawn to. When I look out at the world, when I gaze into the mirror, when I experience anything at all: what is real?

Lately, it seems harder than ever to be sure.

We live in a time when world leaders can dismiss proven facts as fake news while simultaneously alluding to terrorist attacks that never happened, where the free press is owned by the same, small group of white male billionaires, and where hundreds of millions of people experience reality not with their own eyes but through the filter of electronic devices – watching live concerts through their phone screens as they record it or missing a beautiful sunset because they’re busy putting it on Instagram.

They call it the ‘post-truth’ era. The world loves a label, but is life today really that different to any point in the last century? Haven’t politicians, celebrities and the world’s media always lied to us? Before Trump there was Nixon (or perhaps more fittingly, Hitler), before Rupert Murdoch there was William Randolph Hearst, before the Daily Mail and right-wing parties were blaming immigrants for society’s problems, you had countless other persecuted minorities wrongly turned into scapegoats throughout history by one bigoted group or another.

My interest is less in the cyclical nature of history, however, and rather in the elusive nature of truth. I think it was the genius Science Fiction writer Philip K Dick who said that at the core of his books was ‘not art, but truth’. I set out to find the truth in my new book as if it was a precious stone that could be located, unearthed and studied. A prize that, once found, would give up its secrets. The truth I was seeking was a simple one. The story of a man’s life – who he was, where he came from, and what happened to him. And yet, when it came to the famously reclusive artist Ezra Maas, my task was far from simple and nothing was as it seemed.

I didn’t set out to write a biography. I let the story dictate the form. And the true story of Ezra Maas’s life, it seems, was too big for any one genre. You could say it had a mind of its own. It also demanded something from me. If I wanted to know the truth about Ezra Maas – a man of who so few facts were known – I had to be willing to set foot within the pages of the book myself.

Life-writing is a term originally used by Virginia Woolf in A Sketch of the Past, her autobiographical novel which incorporated diaries, letters, travel writing, memoir and more. Interestingly, in the novel Orlando Woolf also merges fiction and biography, blurring the lines between fantasy and her real-life relationship with Vita Sackville-West.

Historical fiction is a hugely popular genre right now. Some argue it has supplanted actual history books, while others warn against the danger of mistaking fiction for fact. Would I advocate reading historical fiction over a history book? No. That’s not the argument I’m making. I’m saying read both. But do so in the knowledge that they are both stories. One of them is just being a little more honest than the other in acknowledging its status as fiction.

History, after all, is simply the authorised version of events. It doesn’t tell us the whole story. Even if we take history at face value, it is still just a record of ‘one thing after another’ to paraphrase Alan Bennett. This is where fiction comes in. History tells us the ‘what’, but it is only through stories that we can begin to understand the ‘why’. It is no coincidence that in cultures all over the world, elders have passed down knowledge in the form of stories for thousands of years.

Bu who can we trust to tell us the truth in today’s world?

I don’t know about you, but more than ever, I’m inclined to turn off the news and open a book. I’d rather knowingly escape the real world than play along with this facsimile of reality. Beyond mere escapism however, I believe there is far greater truth to be found in a story or a work of art than in every social media newsfeed combined.

Stories are not just about sharing knowledge between generations, they have proven psychological benefits as well as their value culturally and historically. Philip Pullman has written how stories are essential for human survival and I wholeheartedly agree. In a world of fake news and alternative facts, stories might just be the key to unlocking ‘real’ truth.

This is just scratching the surface when it comes to the ‘truth’ of course. There are other, more troubling questions if you want to go deeper still. As dangerous as their lies are, most of us know not to trust the words of politicians or the media, but what about ourselves? Can we trust our memories? Our individual perceptions? Does a singular, objective truth even exist?

Everything about the world would suggest otherwise, from language to light. Words are effectively a ‘stand in’ for the real thing. They’re part of an arbitrary system we invented to communicate the world to each other – they are not the truth. Like smart phones – or any intermediary for that matter – language also keeps us once removed from reality. In a different way, light itself hints at a world more complex and more than strange than we realise. It has been shown to exist in multiple potential states simultaneously until it is observed, demonstrating that reality is not fixed, but has many faces depending on who is looking, and that it is strangely linked to perception. If this is accurate, how can there possibly be one truth?

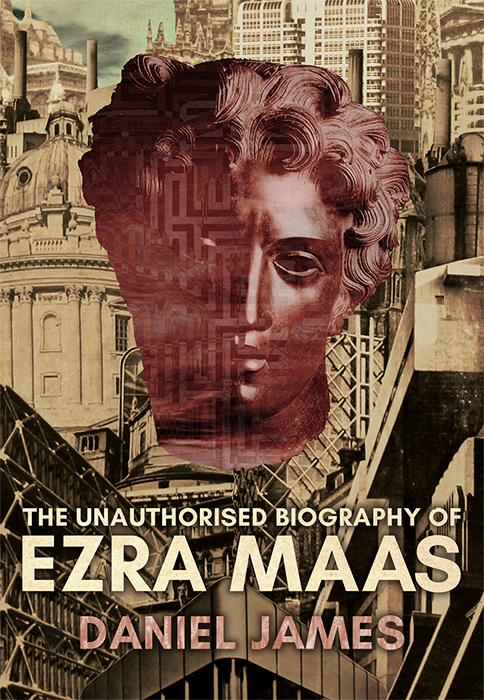

I found myself exploring these questions again and again in The Unauthorised Biography of Ezra Maas. In fact, you could say the very structure of the novel was shaped by such questions. It is an unorthodox hybrid of literary fiction, biography and detective story, written by a former journalist and told through a combination of prose fiction, biographical chapters, news clippings, academic footnotes, emails, phone transcripts and more. Given these origins, the novel occupies a unique space at the intersection between truth and fiction, history and myth.

In order to write such a book, I had to take on different roles, each linked to aspects of my own past lives and former identities – author, journalist, academic researcher and biographer – each offering a unique and alternate perspective on the truth. During the writing of the novel, I had to switch between these roles. As I mentioned, I also found myself playing detective at times, but I’ll come back to that particular role later.

As an author, my primary interest was the story itself. What happens in the beginning, middle and end, who is telling the story and why, and perhaps most importantly, what does it mean? One of my primary goals as a writer is to create a world for readers to explore. When I read a great story, the world around me disappears and my mind is transported to another time and place. It’s one of the most beautiful, magical experiences and it has long been my dream to create a world of my own for others to read about and escape into.

The journalist in me on the other hand has a responsibility to verify the facts and a duty to communicate them plainly to my readers. It’s no secret that journalism is in crisis, from within and without. The industry (even the best examples of it) are discredited on a daily basis by world leaders, it has been rocked by internal scandals and corruption, its aforementioned ownership and the agendas of those pulling the strings are dubious to say the least, and the physical medium it has traditionally been associated with – print – is supposedly dying out.

Despite all of that however, the ideals of journalism and the notion of a free press remain vitally important. True, it’s almost hard to even say the phrase ‘journalistic integrity’ un-ironically these days, but without the few, independent news outlets we have left, we really would be at the mercy of lies and propaganda.

The skills of a journalist are useful to any writer, from an understanding of structure and economy, to the art of good research. This is essential to ground your story in historical reality – very important for a novel set between 1950 and the present – and to provide the kinds of authentic details that will help make the more imaginative sections feel more real.

However, like biography, my book was not content with journalism alone. It had to go further. Just as I never set out to follow in the footsteps of writers like Woolf, I also didn’t knowingly embark on an experiment in ‘gonzo journalism’ – as defined by writer and journalist Hunter S Thompson – by putting myself in the novel (Virginia Woolf’s Orlando crossed with Hunter S Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas – now there’s a pitch!).

If the author is interested in the story and the journalist wants to know the facts, when it comes to the biographer, it is about the life. In particular, it is about recreating a life on the page – a kind of resurrection through words.

Faced with the prospect of writing a biography for Ezra Maas, one of the 20th century’s most secretive and elusive figures, I immersed myself in the genre. I read interviews with celebrated biographies such as Leon Edel, Hermione Lee, David McCullough and Robert Caro (who famously said ‘There is no one truth, but there are an awful lot of objective facts.’) to study their methods and techniques, learning the rules of the game so I could subvert them. Each biographer described their process differently, for some it was like a love affair, for others a literary transfusion, but one commonality was the need to unravel the public and private ‘life-myths’ of your chosen subject to break through to the ‘real’.

Hilary Mantel recently wrote an interesting piece for the Guardian about the ‘myth’ of Princess Diana, an ‘icon only loosely based on the woman born Diana Spencer’. There are countless other examples of course from JFK to Marilyn Monroe. I’ve cited Ernest Hemingway recently as another example of a figure in which the public myth and the private life became blurred. Hemingway, as a writer and self-mythologist, had a part to play in that himself. We’re all guilty of self-mythologizing, but not all of us will find ourselves the subject of a biography. How can a biographer reconcile public and private myths? If we exist in the minds of others as a public figure, if we create and buy into our own personal myths; if people, like reality itself, have many faces, who decides which one is real?

Biographies can be especially difficult when your chosen subject does not want to be written about. Ted Hughes’ legacy has been shielded by a fiercely litigious estate, Byron’s secretary burned his personal letters and Kafka asked for all of his writing and personal correspondence to be destroyed after his death. The subject of a biography can sometimes become the story’s antagonist. Ezra Maas – and certainly his representatives The Maas Foundation – took on this role in my own book.

Ezra Maas himself was challenging because of his absence. He follows a long list of artists and writers who turned their back on fame and disappeared, from literary giants like JD Salinger to lesser known mysterious like 1960s spy writer Adam Diment who reportedly gave Ian Fleming a run for his money only to never be seen again or the lost poet Rosemary Tonks who stopped writing completely and lived in anonymity the rest of her life. Maas was perhaps more like the reclusive writer Thomas Pynchon who did not stop producing art, but chose to do so behind closed doors. (If this is the first time you’ve come across Ezra Maas, you should visit his website www.ezramaas.com or read this excellent feature by David Whetstone for The Journal as an introduction. However, for the full story you’ll have to pre-order my novel.)

The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche said that ‘truths are illusions’ and we have simply forgotten that is what they are. Is truth just an illusion? If we peel back the layers of the onion, one by one, is there nothing at the centre? Why search for something that doesn’t exist at all? And what good are all these abstract questions, however interesting, when as Madonna famously said, we live in a material world? Well, as a writer I believe these questions, abstract or not, are key to breaking through the listless apathy of modern life to ‘the real’. Now, more than ever, we need to shock ourselves into action and ideas that challenge the way we think and force us to question the world we’re presented with can only be a good thing.

As for why search for something that might not exist? First of all, I can’t tell you if the truth does or doesn’t exist. I think that’s something we each have to find out for ourselves, on our own paths to our own particular truths. Secondly, I think we search because the act of searching itself is important. We must continue to question the world and look for answers. We must not take anything for granted, whether it’s the words of politicians, the physical world as we perceive it, or even our own memories.

I mentioned earlier that I found myself playing detective during the writing of my book. There is much we can learn from detectives and the way they question the world. Their investigations echo the work of both writer and reader as they search for the truth, connect the evidence and attempt to uncover what has been lost or concealed. I have written an article specifically on this subject, and my love of detective fiction generally, for my publisher Dead Ink Books. You can read it here.

In the end, it comes back to the truth. By drawing on my past and present as a writer and journalist; taking on the roles of accidental biographer and literary detective; and drilling down through 70 years of myth and history, did I discover the truth about Ezra Maas?

You didn’t really think I was going to tell you here, did you? You will, of course, have to read the book to find out – and if you’re interested you can pre-order it here until 31 August, or buy it in all good book shops later in the year. Maybe you’ll find the truth inside its pages, perhaps you’ll find more questions, but either way I hope you enjoy the search. Just like the truth itself, I believe everyone makes a book their own and creates their own personal connection to the text. Above all else, if you happen to find yourself holding a copy of The Unauthorised Biography of Ezra Maas, I hope you will discover the one thing everyone should find waiting for them inside a book – a great story; the kind that takes you far from the hollow shores of the everyday in search of forbidden knowledge and hidden truths.

Daniel James is a writer and journalist from Newcastle. His debut novel, The Unauthorised Biography of Ezra Maas, will be published by Dead Ink Books in November 2017. A crowdfunding campaign to help support the novel is currently underway via pre-orders of the book. To help make Daniel’s novel a reality, simply pre-order a copy of the book before 31 August 2017 from: www.deadinkbooks.com/crowdfund