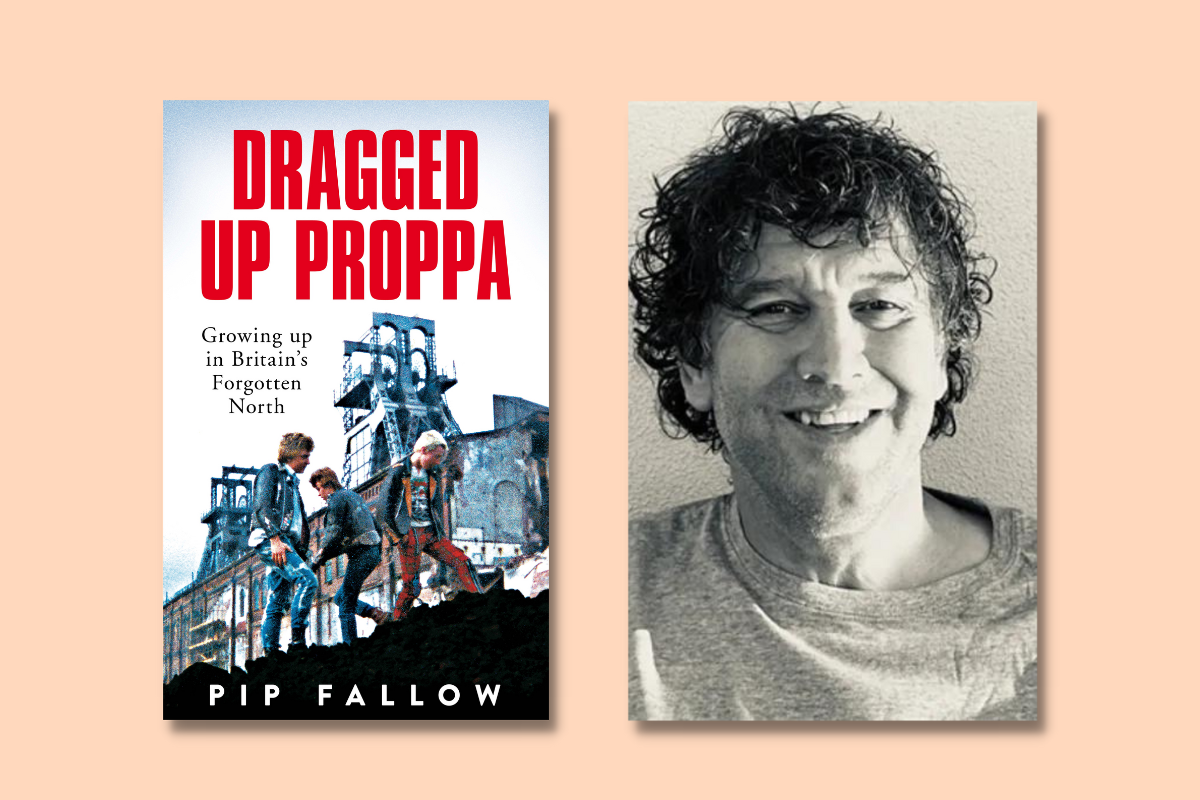

Dragged Up Proppa: Interview with Pip Fallow

Pip Fallow’s memoir Dragged Up Proppa is the story of growing up working class in a forgotten England. In this interview we chat to the author about his experience writing the book and the themes within it.

Margot Miltenberger: In your book you talk about how you are always writing. Sometimes even staying up past your 1 o’clock deadline! How long have you been working on this book, and has it turned out the way you expected?

Pip Fallow: Your question makes it sound like sometimes I write and other times I don’t. That’s not the case. If I’m awake I’m writing; in fact, some of my ideas come from jagged dreams that startle me and break my sleep. I jolt up and jot them down. I don’t have to be at my laptop or pushing a pen to qualify as writing, I could be walking my dogs, planting veg in the garden, or laying bricks in the rain, my brain is always working with words. I wrote, in this book I believe, that ‘despite me being illiterate until my mid-thirties I’ve always felt I have written, there was just a time I couldn’t get it down on paper.’ I suppose this make me sound tormented. I’m not. Or, if I am, it’s fine, I know no different.

As for, ‘how long have I worked on this book?’ Well, there’s thoughts hidden in its pages I’ve had stored in my minds library since childhood so one could argue it’s a lifetime’s work. However, the actual physical, from-brain-to-paper, process from start to finish of this particular book was about three years. Might have still been writing it now if my editor hadn’t hit me with a big stick and told me put a full stop on it. I’m pleased he did, less is more, he reckons, and I think it turned out quite well. Clever people these ‘educated folk!’

MM: You were highly commended for the Sid Chaplin Award in 2019. Can you tell us a bit about your journey from before you got the award to what happened afterwards?

PF: Well, it all started with a book I wrote about three young poorly educated pigeon fanciers from Durham who fell out of school just after the bitter 1984/5 miner’s strike. Just as they are coming to terms to the stark reality of the coal industry being put to death by Maggie, they are dragged into the benefits office and are told they must work for their dole on Youth Training Schemes (YTS, remember them?) After six months, we see them developing a little self-worth as they get settled into a work routine before watching all three get sacked on the same Friday as their employers replace each one of them with another free sucker from a dole queue of four and a half million. Disgruntled with Thatcher’s Britain, they meet in the old caravan at their allotment and hatch plan B. A very ambitious robbery. They plan it for months and pull it off, get the dosh, but there’s a wee twist as things don’t quite turn out as they hoped.

A bit weird, probably, but I thought it a good tale. By pure chance, I met a man at a funeral, got chatting and he recommended I should enter it into a competition. He put me in contact with a friend of his who helped me put a two-thousand-word piece of the book into the Sid Chaplin Awards and I was highly commended. After that, it seems my feet have hardly touched the ground. I bought a laptop with the prize money and learned how to use it. I was sponsored by the Arts Council. Given tuition and assigned an agent.

The first thing my agent did was to sit me down and ask me where the story of the three boys had come from.

“Well, it’s true, it was me and a couple of mates of mine,” I explained.

“I think you need to start writing a memoir!” he smiled.

I didn’t know what a memoir was.

MM: You describe some impactful scenes from your childhood, for example, your father using his headlamp to search for your cheap plastic sandal in the mud late at night. As a writer, how did you decide which scenes to include or exclude? In other words, how does someone setting out to write a memoir fit their life into a book?

PF: I believe reactions to situations, rather than the situations themselves tell the tale. The situation is merely the backdrop to the scene but once the scene is set, I’d like to think, what the reader is really thinking is, ‘So what did you say?’ ‘What did you do?’ ‘How did you feel?’ I could write hundreds of stories about being poor but that would just be an inert list of unfortunate circumstances. It’s what you do with the hand you’re dealt that draws intrigue. It is for me anyway, and that’s probably why I just told a few selected yarns. Once the reader hears my take on a few different scenarios and sees me deal with them my way, it’s up to them whether they get me or not.

MM: The content is about your own life, but of course you include historical context and family stories. Did you have to do much research to supplement your memory?

No, if there is one talent I have it is, I forget nowt. People I attended school with have read the book and say, ‘I was right there, back in the classroom, how could you possibly remember so much?’ Yet I think, ‘How could you forget?’ I can recall relatively unremarkable conversations from many years ago. That’s probably why I could never fall out with myself. I would never let me live it down.

MM: You describe looking up at the pithead as a child and feeling the sense that you were on a conveyer belt sucking you towards the pit. At the end of the book, you write beautifully about the mixed feelings you have now – that you hated the pullies, and yet you long to see them. You saw your father go down into the pit and had every reason to believe this was to be your life trajectory. What would you tell other people who have a story to tell, whose perspective has not been heard because they live in the north or any other excluded community?

PF: Writing about myself was the hardest writing I have done. Not because of all this ‘Oh, one must dig deep into one’s inner soul and spill all one’s emotions out bare for all to see,’ bollocks. That was the easy bit. The reason it was hard for me to write was because I didn’t believe I or it was interesting.

My big awakening came when I was halfway through being almost forced to write my memoir. The Arts Council money I’d won had me sitting in the reading rooms of some arts centre in Edinburgh being mentored. I got talking to a lad who was there for the same reason. Thinking back now I reckon we had probably been put in the same room on purpose.

He told me of his life. His mother and father had both died of heroine overdoses in the same month when he was eight years old. He had a brother of twenty-one who was also a drug user and dealer and after their parents died, they continued to live as before in one room they rented above a busy pub in Edinburgh City. His daily routine would be to rise early, walk around the railway station, nick a handbag or a purse or some luggage, go around his contacts, sell what he had stolen, return to the pub, pay the landlord the daily tenner for the room, wake his brother, give him the money needed for his morning fix and then go out and feed himself with what he had left.

After a couple of years of this, his brother announced he needed help to pull off a burglary. One of the main drug dealers in the city had decided to go on holiday and as the older brother knew he had just received a large consignment of drugs his house was to be hit.

This guy, who was now about thirty-years-old sat, in front of me and told me how it was his job, as a boy of ten, to scale the front of this huge mansion, crack open the doors to the front veranda, go down the stairs and open the front door for his brother. It worked and they ransacked the house. His information had been right and they found a huge consignment of drugs hidden upstairs, piles of cash and lots of jewellery. When they came back down the stairs, they were confronted by the drug dealer’s wife. She had been sleeping on the sofa.

“Why are you two in my house?” she asked. She had been in the car with her husband when he did his drops in the city and recognised the boys instantly.

“What did you do?” I asked.

“My brother strangled her to death, right there in her own living room.” He explained.

“Did he go to jail?” I asked.

“No,” he smiled. “Nowt that nice ever happened to us, he went out dealing about a week later and I never seen him again. At the bottom of the North Sea with concrete boots on, I reckon.”

“What did you do?” I asked.

“Well life became simple, there was only one to look after, me. I got bored and got the landlord of the pub to pretend he was me Dar and he got me started at a local school at twelve. That’s where I learned all this reading and writing shite!” he announced.

“So why are you here today?” I asked.

“They want me to write about me life,” he looked bewildered. “Who the fuck wants to read about me rotting away in a shit hole bedsit here in Edinburgh, I don’t know!” he laughed shaking his head.

I found it easier to write after that. I was not me I was writing about, but a time and place that had come and gone but needed documenting. It didn’t matter about me bearing my soul, I was irrelevant. Just a writer with a duty to tell.

Dragged Up Proppa is published on 23 March with Pan Macmillan. We have three copies of Dragged Up Proppa to give away!

For the chance to win, tell us what you’re reading on Twitter, Instagram or Facebook using the hashtags #NorthernBookshelf and #DraggedUpProppa. Winners will be drawn on 24 March 2023.