Researching Common People

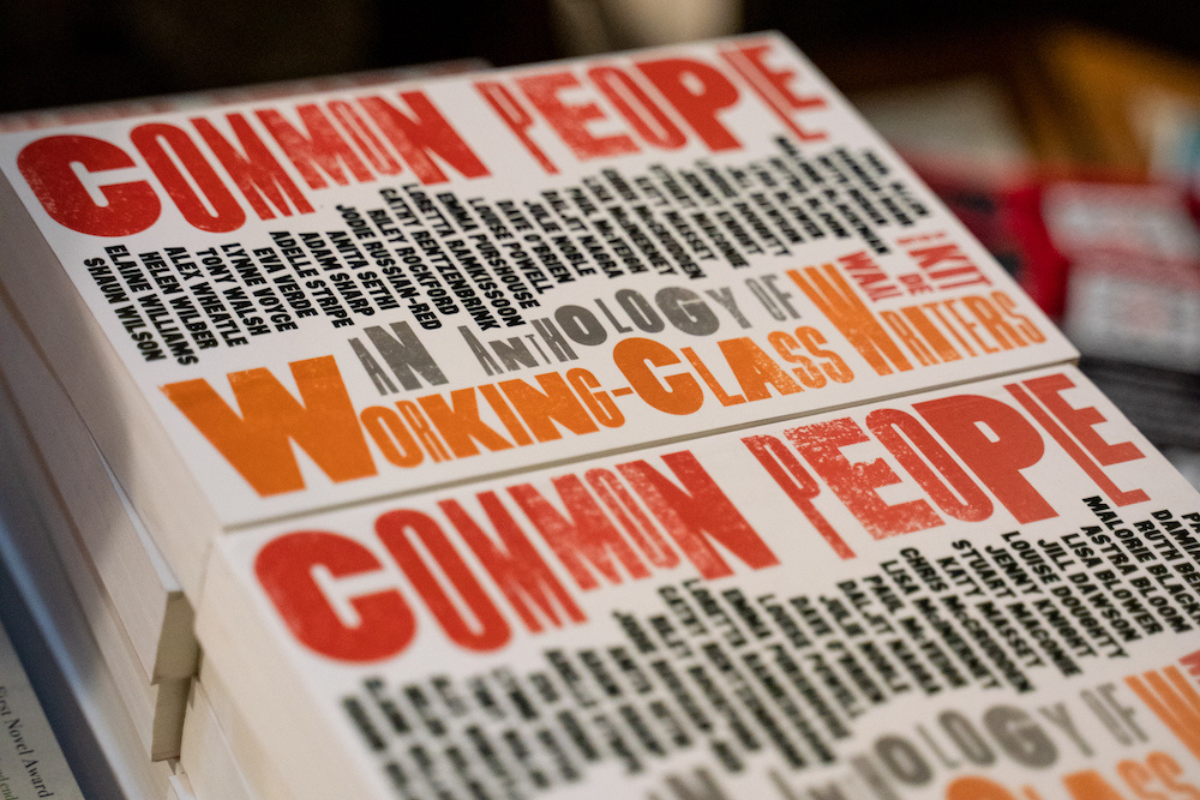

As part of a decade-long partnership between New Writing North and Northumbria University, Katherine Greenwood is researching contemporary writing by and about the working classes, with a particular focus on the Common People anthology published in 2019. Inspired by the anthology’s project to ‘reclaim and redefine what it means to be working class’, Katherine has been considering the ways that Common People rewrites the working-class story for the twenty-first century. Read about Katherine’s research below.

My PhD research is a critical study of contemporary writing by and about the working classes, with a deep dive into the 2019 Common People anthology edited by Kit de Waal. I am working with a selection of the writers from the anthology, listening carefully to their words in interview and on the page, unpicking the nuances and complexities of their stories.

The working classes are under-represented in the twenty-first-century literary industries, both in the workforce and in the books we produce. This is a major problem recognised by publishers, Arts Council England, and UK government.

Part of the issue is that the working classes tend to be understood in society and culture in terms which are outdated and one-dimensional, either romanticised or stigmatised. Ideas of, for example, the ‘heroic worker’ or the ‘chav’ steamroller over a vast diversity of experience which is continually evolving. In literature, ‘working-class writing’ is too often assumed to be grim and gritty, largely northern, urban stories of toil and hardship.

Taking the Common People anthology as a snapshot of working-class writing in the twenty-first century, my research examines – in relation to wider trends in this emerging field of contemporary literature – some of the ways that these writers reshape understandings of class experiences in society today. It’s not about making sweeping statements or pretending to be conclusive. I could not hope to capture all the working-class stories in post-millennial Britain in one, or a thousand PhDs – and both the curse and the thrill of studying the contemporary is that it is constantly shifting and developing. I am studying living authors, and my research methods – involving interviews and surveys – reflect the need to give writers agency to speak, to articulate their own, active experiences.

Yet it is also possible to connect personal experience to the big narratives of societal change, to sift out what is new about working-class representation in these stories following a period of profound social, economic, and political change in Britain. For example, the collection registers the ways that working life has been transformed over the last fifty years, showing that the manual labour of an industrial economy has largely disappeared. Today’s working classes are much more likely to be employed in the sales and service industries, often in the insecure contracts prevalent in contemporary times.

Clearly, work is a key aspect of working-class life: the clue is in the name. It is the need to be productive, to earn, that defines this sector of society. Yet, as Common People shows, working-class culture and identity is about so much more than toil. Considering a broad shift away from work in understanding working-class experience today, one strand of the research examines the working classes at home in Common People, showing that class is felt and shaped in childhood and in the domestic spaces of our everyday lives. The anthology also focuses less on work, and more on play, highlighting the place of pleasure in lives that might be tough but also bright with joy – and that leisure and pleasure are political, with stories of women enjoying traditionally male pursuits like playing darts and pool, watching football, and going to the dogs. In a contemporary context of scarce and precarious work, I explore whether it might increasingly be in leisure that a sense of working-class purpose and togetherness can be found. In a final stage of the research, against gloomy talk of the decline of community and the polarisation of working-class thought, I am studying new iterations of working-class solidarity or community represented in the collection and what grounds we might have for hope.

Common People points to an understanding of working-class experience that is highly subjective and infinitely varied. It points also to a culture that is rich, vital, and something to be celebrated. The collection shows that working-class life doesn’t always happen up north and in urban areas; that it is not always about miners, football hooligans, or the dispossessed and the destitute. Stories from across the UK depict the lives of not only urban dwellers but the rural working classes, as well as those from the cities revelling in our green spaces. The anthology also demonstrates that class is deeply intersectional, meaning that it operates in alliance with other aspects of a person’s identity such as their gender, race, and sexuality.

Rewriting the working-class story is, in part, about making that plural: stories. I’ll give the last word to the memoirist and novelist Cathy Rentzenbrink, who spoke to me in an interview about the need to listen to a diversity of voices, expressing powerfully the value of literature in articulating the truth of experience and the reality of individual lives:

‘What do we really write for? For me it has to be about trying to find meaning and purpose, and it has to be about trying to communicate honesty; it has to be about trying to find a way to say: I was here in this world, and this is what I saw.’

Katherine Greenwood is studying for a Collaborative Doctoral Award at Northumbria University in partnership with New Writing North.

Follow on Twitter @KatherineLucyG @NorthumbriaUni @NewWritingNorth.

Report links: