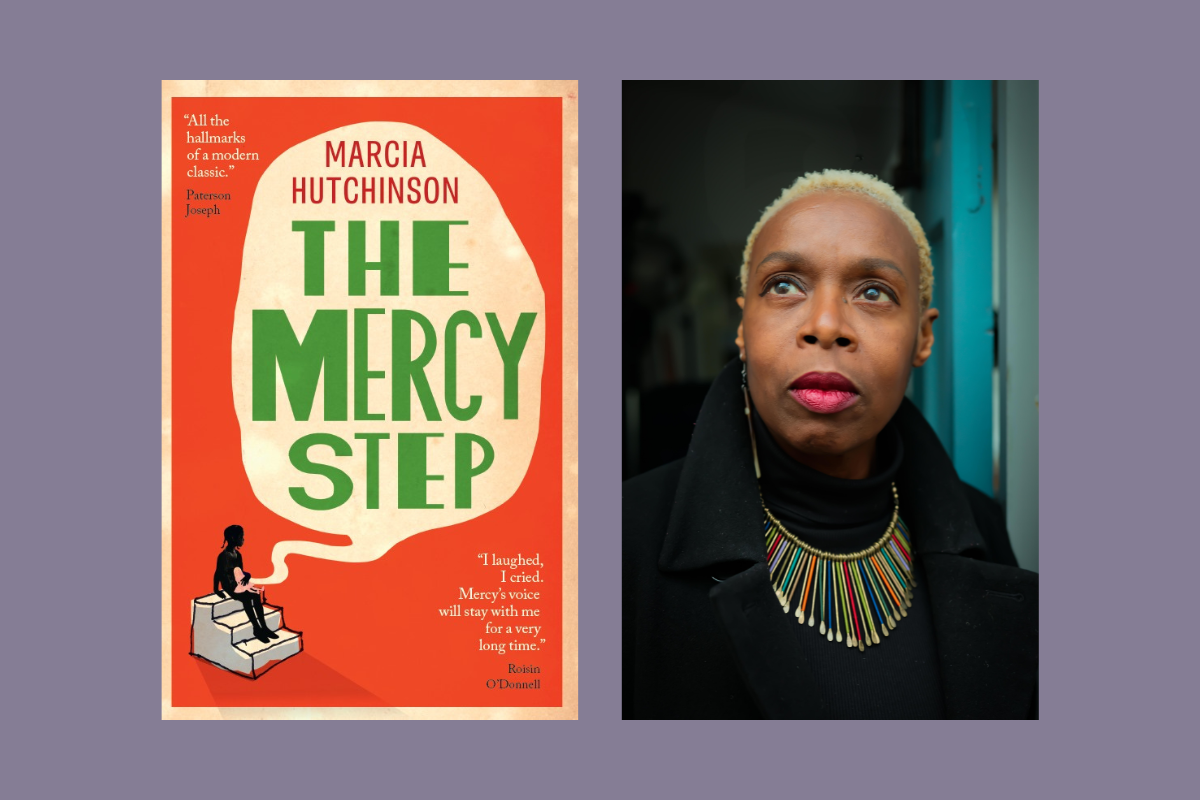

The Mercy Step: Interview with Marcia Hutchinson

The Mercy Step, Marcia Hutchinson’s solo literary debut, is a sharply-witted and tender portrait of a young girl’s quiet rebellion, and her refusal to be broken, as she grows up in 1960s Bradford. In this interview, Marcia shares about her experience becoming a full-time writer later in life and the therapeutic power of revisiting her childhood through storytelling. Learn about how she dictated chapters of her book while out dog-walking, her decision to write fiction instead of memoir, and the daring hope that runs through The Mercy Step.

Your journey to being a published writer comes after a long and varied career in law, educational publishing, and politics. What led you to pursue full-time writing at this point in your life?

I’ve been writing since I left university but life got in the way. I had children, started an educational publishing business and gradually drifted more towards arts admin than my own creative practice. I think gradually I treated publication like a dream that some thing boys have of becoming a professional football player. I thought I was too old for it. The thing that led me to pursue full-time writing was becoming single at the age of fifty-five. With no children or partner to worry about, and a level of financial independence which meant I could work part-time, I could really devote myself to writing. I found a local writing group, Cultureword, and began attending every Wednesday. That meant I had to have something to read out each week and it absolutely got me producing work regularly. The encouragement I received at the group was phenomenal. I was initially writing short stories but I got so much positive feedback and encouragement to turn it into a novel I began to believe that I had talent and I could write.

Earlier this year, you published The Blackbirds of St Giles with co-writer Kate Griffin. What’s been different about writing and publishing as a solo author for The Mercy Step?

Writing with a co-author and solo writing are as different as chalk and cheese. When writing by myself I come up with the ideas without discussion with anyone else. I hadn’t intended to be an auto-fiction writer but the advantage of writing at my age is that I have so many stories from my childhood (and adult-hood) to “choose” from. I think I’m also working through a fair chunk of trauma and trying to understand its impact on me. With my own creative writing I’m seeking answers but sometimes I don’t even know the questions.

With The Blackbirds of Saint Giles, Kate and I were effectively commissioned to write a novel based on an initial idea from someone else so we already knew the period we would be writing about and who the main character would be. Writing The Mercy Step was very much me deciding to examine my childhood and try and make it make sense.

It was a pleasure to spend 300 pages in the company of young Mercy, whose voice is imaginative and completely compelling. Tell us a bit about where Mercy came from, and the process of developing her character and story.

I honestly didn’t consciously make a decision about the process of developing Mercy’s character or story. It started life as a series of short stories, each one an exploration of an incident of which I had a vague memory as a child. Where I couldn’t remember actual details I simply made them up. I wanted to get into the mind of my younger self and see the world from her perspective. In some ways the process of writing The Mercy Step was me allowing my subconscious to write on my behalf. The chapters came best when I dictated them. I would take my phone and the dog and walk around the local park dictating straight into Google Docs. Each chapter would take less than an hour for a first draft. When I got back home I would go over what I had written and in all honesty I was sometimes surprised at what came out. Memories that had laid buried for decades had bubbled their way up through my psyche to reach the surface through the filter of my creativity. This meant that the final novel isn’t a faithful retelling of the past. I was trying to remain in that liminal space between dreaming and waking, conscious enough to write but not so conscious that the creativity was stifled.

Mercy’s story draws parallels to your own upbringing in Bradford with Windrush generation Jamaican parents. What was it like revisiting your childhood through writing The Mercy Step? And why did you choose to do it through fiction, rather than a non-fiction form?

I knew that I didn’t want to write a memoir and specifically I didn’t want to write a ‘misery memoir’ because I don’t really enjoy writing that deliberately toys with the reader’s emotions. Also I didn’t think I could remember enough details about my childhood to write a memoir or an autobiography. By writing fiction I freed myself from the need to be accurate and could just focus on creativity, telling a good story. I had no idea that some of the stories were funny until I read them to my writing group and they laughed in parts. Revisiting my childhood through writing was like being therapist and client simultaneously. There were many times I had to stop and cry before I could carry on. It was like I was a miner digging for coal and that coal was my own emotions. I suppose I was trying to make my childhood mean something and if I could create literature out of it then it had meaning. Also I think everyone at some point has felt the outsider in their family and I wanted to capture that universal theme, of being the child in the corner watching and waiting but never quite feeling like they fit in.

The Mercy Step explores Windrush-era immigration, racism, domestic violence, religion, and mother-daughter relationships, all through the eyes of a child and often in stark contrast to her pure-hearted childhood innocence. How did you approach writing about such complex and often dark subjects from a child’s perspective?

Asking me how I approach writing such complex and dark subjects from a child’s perspective is very difficult because I don’t think I ever did look at it from a child’s perspective. I feel as if I am an old soul, an adult born in the body of a child and trying to make the world around me see sense. That is Mercy’s dilemma – she knows that what is going on around her is not right but she doesn’t have the power to do anything about it. I am still Mercy and Mercy is still me and I am still trying to right wrongs. In some ways the best part of writing Mercy was not trying in any conscious way to address any particular theme. I just wrote and let the chips fall where they may. It was only when readers told me that I’d been addressing these ‘dark’ subjects that I was able to say, ‘oh yes I suppose you’re right,’ but for me it was not conscious at the time of writing.

Long-time book lovers will smile when they see Mercy discover the wonder of Carlisle Road Library for the first time, and will relate to the profound escapism and empowerment she finds in books. Can you tell us about the impact of reading in your life, and perhaps share some of your favourite childhood books?

For me books and reading were all about escapism. I say books – it’s hard for me to share my childhood books because I didn’t have any. I don’t recall there being any books in my childhood home other than the Bible. For me as a child reading was escapism and I would read anything I could get my hands on, whether it’s the back of a cereal packet, the instructions on the washing powder or the newspaper. I remember being thrilled when I was old enough to understand what I was reading in the King James Bible and getting a buzz out of stories like the Israelites escaping from Babylon. I tended to read factual books when I was a child, such as the Ladybird Book of Greek Mythology, or Janet and John reading books. For a writer I am hideously poorly read.

And finally, what do you hope readers will take away from the story?

Just that, “hope”. As long as you are alive, as long as there is still breath in your body, there is still hope. No matter how much Mercy’s father tried, he could not crush her spirit. When I read about people who have gone through hideous things and onlookers say that their life has been ruined I never believe that. While you are still alive there is still hope, and you can make something of whatever circumstance you find yourself in. Even if it’s outbidding your debut novel in your sixties.

Purchase The Mercy Step through our Bookshop affiliate link

The Mercy Step is published on 22 July 2025 with Cassava Republic, and we have two copies to give away!

For a chance to win, tell us what you’re reading on Instagram, Facebook, Bluesky or X using the hashtags #TheMercyStep and #NorthernBookshelf. Winners will be drawn on 11 July 2025.